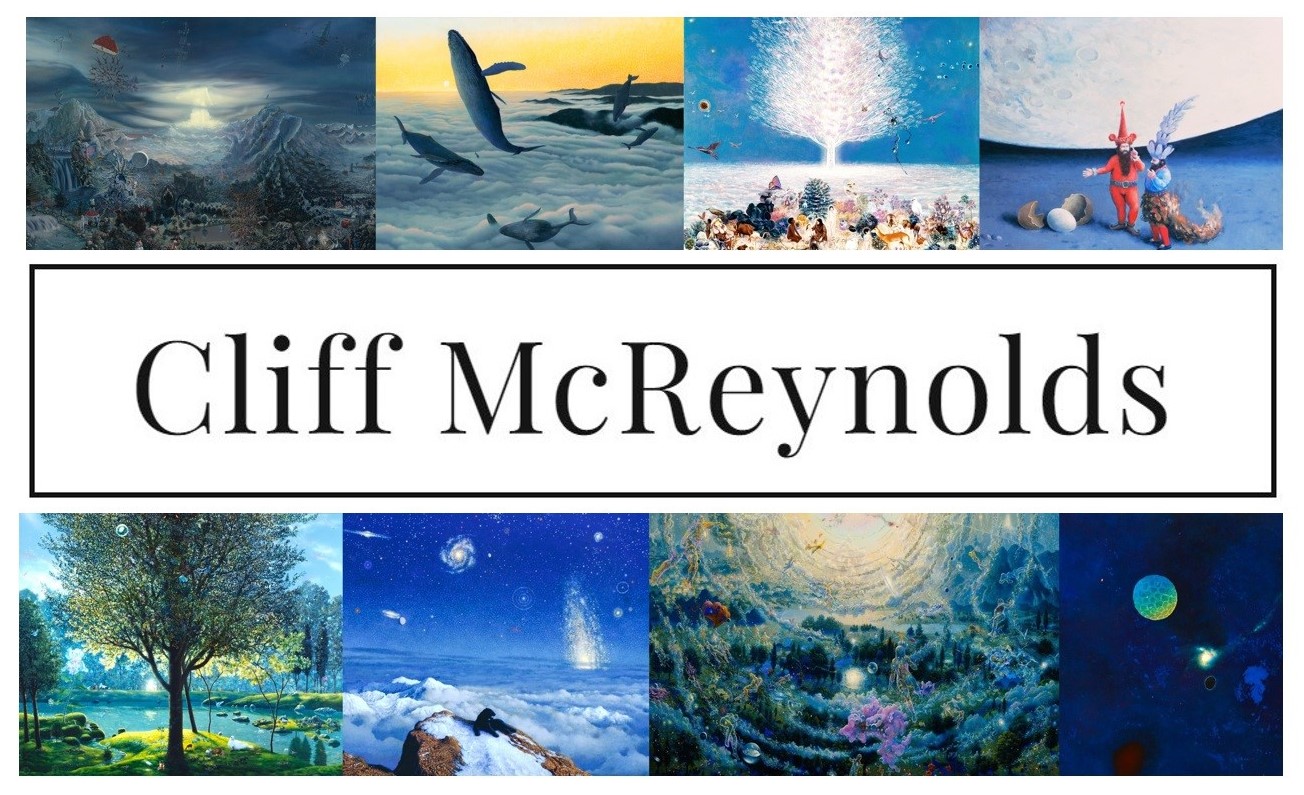

Written By: Cliff McReynolds

(first published by Alden Mills Pub., Feb. 1988, pp. 27-29)

Image: Opening Night At Hirshein-Gebtune 1988 (graphite/paper) © Cliff McReynolds

Wonders of the Visible World (New art museum is causing controversy; huge

erection pleases some, offends others)

The inaugural biennial at the just-completed Hirsheim-Gebtune may not have any redeeming social value; but in an era which dotes on equality among subjective realities (no matter how curious or vile) it is probably fitting that a museum purporting to survey the contemporary art scene should itself reflect the art which reflects the culture.

The building, designed by Max Zicon-Withpit, confronts us with uncompromising eclecticism that ranges from classical Greek to the wigwams of the Iroquois; in a sort of “why not?” approach to architectural design which serves notice that here is one more architect with an original vision, while affirming that 39.2 million dollars and 782,000 square feet of floor space can be fun.

The entrances are indicative; there are 16 of them but only one is open at any given time. That one entrance is subject to closure without prior notice. It often is, so that another may be opened elsewhere. Although posted signs state which entrance is open, they are inaccurate. This is why one may regularly observe frowning herds of ticket holders wandering from one entrance to another.

Those who actually gain admittance may notice other facets of personal statement. The walls are constructed at a 45° angle, which would create serious problems for the curator hoping to hang paintings. Alas, that was not meant to be; the walls are studded with hundreds of weathered railroad ties jutting from all angles, creating a blinding compositional drama in the revolving light of powerful starch lights glaring out from among them. The display of sculpture has also proven an insurmountable challenge. The floors have beets inspired by a meaningful personal experience which the artist does not discuss except by allusion to a subsequent obsession; that the floors of the museum could only be lacquered panty hose constructed to resemble the Atlantic off Cape Hatteras in a storm.

Zicon-Withpic has often emphasized how much he loves his work. Nevertheless, he treats a building as an object, an approach which some feel reduces the union of art with edifice to an act of passion. Perhaps. In this instance, however, It seems apparent that only a will undistracted by complicating entanglements could thrust the instrument of its own justification into that higher emancipation where the climatic surge of a supreme self-expression could, at last, release architectural form from function.

Since display of the exhibition would be impractical within the actual museum, it has been mounted instead on the canvas walls and dirt floors of two full-sized circus tents purchased for that purpose, as well a for display of the permanent collection.

The scope of this first biennial, though ambitious and wide-ranging, cannot pretend to represent more than a few hundred of the myriad directions artists are exploring in this new age of artistic pluralism. And, yet, a number of artists, burrowing ever deeper into the concentric circles of their deepest depths, continue to establish differences between their work and that of their peers by reaching beyond the usual new and original departures to reconnoiter the somewhat less traveled realm of unusual originality.

Although “crypto-red unctionism” has been a recurring impulse among the northern Iconoclasts in many of the post-modernist schools, no one until Heinz Ilcterbaum ever commanded the technological means – not to mention the brio and single-minded determination to validate its premises. His “Au Revoir Chartres,” documented here with correspondence, working drawings, before and after photographs of the cathedral and a selected list of indictments, may one day be regarded as a pivotal catalyzing development in the evolution of the post-structural era as he envisions it. Indeed, If the vision finds its means, then we may also be sure that the means points the vision to its proper end, even when certain procedures toward that end cause grumbling or disapproval.

Dieterbaum had previously worked mostly with Jack hammer and wrecking ball, but the enormous scale of the present piece compelled consideration of tools with greater fire power. According to his computations, seven 105 mm howitzers, correctly placed and expertly manned, could complete the work in a six-hour time frame. In fact, It took almost four days, because ‘ of the unexpectedly spirited efforts of French gendarmes (and a civilian ad hoc force) to place limits on Dieterbaum’s freedom of artistic expression.

In a similar vein, John Smith (his nom d’art) raises questions relating to artistic freedom with “Big Deal.” Does the right of free speech guaranteed by the First Amendment include the artist’s right to express himself aesthetically, unimpeded by legal restrictions? Does the artist have the right to refuse entry to his creation when it is displayed In a public setting? These and other questions will apparently be settled in court; a suit brought by the city attorney’s office against Mr. Smith and the Hirsheim-Gebrune is scheduled to reach trial next March.

The polemical nature of “Big Deal” reminds us that the formal parameters of the creative process are usually most tenuous when they seem most secure; relativity then becomes a movable beast (as Hemingway almost said). When the consensus of one generation becomes the intolerable impediment of the next, art becomes the branch that waves the winds of change.

Change, of course, Is discomfiting and problematical. It involves the unknown, the fearful, the mysterious. So does Mr. Smith’s work. And despite the intense curiosity of a perplexed public, the enigma has remained, in part because no matter how creative or persistent, no one was ever able to view the interior without fulfilling certain requirements.

From the outside, “Big Deal” appeared to be a huge mobile van shaped rather like a long armored truck. It was powered by a 3,000 HP Pratt and Whitney J.L engine, and had a small windshield and portholes of one-way bulletproof glass. No one was admitted inside without a large bundle of cash and/or close questioning, and no press or law enforcement, period.

By special arrangement with the museum, “Big Deal” was placed at the main exit of Tent II, and Mr. Smith given permission to drive away in his exhibit at any time without prior notice. Around 2 a.m., Thursday morning, he did, just as Sheriff’s deputies, according to reports, were arriving at the Tent II entrance with search warrants.

Thus, the aura of the mystical at its core – that unearthly quality of Inventive will which must always defy ordinary limits In order to break into the attainment of a higher order of originality – implies that a condensation of experiential particulars, i.e., the swift transaction, or the sudden paranoia, has been intermingled with the artist’s intent to create the sort of unique encounter with previously undisclosed levels of instinctive reality which is the essence of the aesthetic experience whenever It occurs. Perhaps this must suffice, since not only the mystery, but the Intention of the work of art may be diminished or perverted by attempts at full disclosure by the artist, definition by the critic or adjudication by the courts.

“Broom IV,” by Zap Flant, is the sixth in his latest cycle of assemblages, all of which tend to mediate and ratify the felt nature and physical existence of the objects he selects. Although the present work, a broom leaning against a wall, may still generate a keener honing of the artist’s metaphysical itinerary, Flant has not yet expanded his sensibility to Include the ramifications of a philosophy formulated outside the indicative mood. But why quibble? The progression of his beguiling solutions reflect a simulated vision of definitions from statements connoting negation to assertions intersecting their proper function as signifiers, or bridges as it were, across the lush terrain of an eminent Interior transcendence.

Recall that even in the early ’70s, when Flant first produced the flamboyant “Trios,” he was already intimating the possibility of extending his oeuvre to encompass additional reductionist proclivities, as indeed he later did with “Duo” and “Trio Minus One” aeries. By late 1978, not only was he placing a rock, a pair of sunglasses and a shower curtain on the floor of a gallery, for example, he was sometimes removing the shower curtain. It was this counter-elaboration of expression implicit in the condensing of his means which unleashed that unexpected primordial tension of the various “Duos” and “Trios Minus Ones.” It is this same characteristic tension which Flant continues to tap as the activation mechanism for virtually all the work he has subsequently produced. As he puts it: “Well, I just thought when I felt like I was doing the other things, I was like a free trip to the movies, but then I had that period when I was licking fly swatters, and I dreamed this would not be the wave of the future so now I eat the whole tomato and so on…”

We find this progression provocatively extended In the work of Blakely Potter, although the aggressive sullenness which his “Blink, But Flinch Not” evokes probably relates less to its nature than to its presumed location. By reinterpreting the formulaic amenities of spatial relationships in the light of his own existential concept of presence, Potter implies a denser texture of motives and ontological assumptions on his part, while inducing a heightened sense of inquiry on ours.

In terms of formal composition, the space around objects has traditionally been assigned an Importance equal to the objects themselves. However, by merely subtracting the object, Potter compels us to refocus, to involve ourselves with the idea of an object, a process which suggests the art object need not necessarily be the art, but rather, serve as the vehicle for the experience of the art.

Thus, a space may appear as a void (a void to enter), an extrapolation of sublimations alluding metaphorically, perhaps, to the maleness of projection through the guarded gate of another’s receptive vacuum. If so, this is art in the service of acceptance, of liberation, a work which speaks to the affirmation – finally – of men who wear dresses, or would like to.

Too often, the collision of attraction with inhibition means entropy; by the time one is ready to rationalize the matter, the means has ceased to exist. But here we find one of those rare occasions when art informs life rather than simply mirroring it, and we sense that the exhilarating rush of eternity is more a probing kind of static, a realization which compels us to strip away the clothing of symbiology to receive the essence of the message; when universal principles become inconvenient, emptiness and substance may become interchangeable among aesthetic value systems, free associations and consenting adults.

There are some, of course, who may no longer trust the artists to make art. Empiricists and certain traditionalists, for example, might want to suggest that art which excludes mere existence as a condition of Its reality would have difficulty attracting an audience to relate to it, search for it or even maintain the concentration required to explore the rhetoric of its didactic. However, skeptics do well to remember, as the history of art in this century repeatedly demonstrates, that today’s trash is tomorrow’s smash. Furthermore, as people mill around Flant’s work (i.e., “The Name Tag”), the discerning may already see telltale signs of that classic combination of testy bewilderment and awed intimidation masked as polite interest or good-matured contempt which traditionally precedes international recognition for the artists, validation for his art and, naturally, Increased sales.

While It is hardly possible any longer to group artists according to plausible “Isms,” there are still some who pick up threads from past movements even as they slide courageously (and painfully, one assumes) around out there on the cutting edge of the avant-garde. Vestiges of futurism, for example, an early expression of the impact of machines upon culture, arc still found in the work of Jack Slack, the New York building ascensionist and Samantha Mill Valley, whose “Earth, Sand, Rain, Peace” maybe seen In Tent I opposite “Ant Wars XIV” by Dooley Simms.

Ms. Mill Valley’s reaction to those disembodied recorded voices we sometimes hear when picking up a ringing telephone has been to create her own series of recorded responses, activated by audio tone recognition, so that her machine interacts with their machine. The whole device is constructed of seashells and celestial dust, weighs “less than a basket of rose petals” and is suspended 15 feet above the ground by positive thought and harmonic premonitions.

While the incoming messages are uniformly pedestrian, Mill Valley’s recorded reactions combine with them to create 2 surrealistic, almost mystical interplay of technology with emotional complicities and informal ideological positions. One mechanical caller offers, free, “three days and one night in Las Vegas.” Another offers congratulations on winning either a Porsche 911, a beach-front cottage in Sausalito or a set of steak knives. In reply we hear: “I am me . . . Vegetables are animals, too… Let the water run-with joyful feet. . .” Responses are sometimes smug, chanted, accompanied by beetle chimes, or by the sound of one eye looking. The point is obvious: this juxtaposition of vernacular narratives postulates the displacement of decontextualized appropriations of time, of distance, of space, segueing to a transformation of revitalized technological propensities ranging from a kind of overbearing passiveness to a fragile, loving vengeance modified by the forthright ambiguity of a gynecocratic refulgence of power, of purpose, of predaciousness which seems marginally mitigated by her suspicious tendency to use small words where large ones would suffice.

Nevertheless, Ms. Mill Valley seems positively aglow with the promise of her projected schema; in addition to continually dueling with technology, she hopes to help reestablish the ecological balance by removing unenlightened vibrations from the food chain. This process can be facilitated, she feels, by following the teaching of Hrka Mikovilc, a 7th century coven member from Lapland, now in her 142nd Incarnation, who speaks through Whey Uthustra, a trans-channeler living in San Francisco. According to Uthustra, Mikovlic has returned to help us understand that her teaching has superseded God’s because it is older but newer, and that we may become as one with the two souls of the three eternalness’s by returning animal skins to their rightful owners, learning to milk reindeer, and, above all, remembering to manifest new astral spheres Into the flow of our meditation each day, so that we may resonate with the universal energy of cosmic niceness.

Varying “religious” concerns emerge as a recurring theme of the entire exhibit. We find a large computer, shaped like a cross, plugged directly Into the checking accounts of over 374,000 “prayer partners” whose faith and generosity support the an and tanker fleet ministries of Happyjack Humbly. One also notes, in an apparent gesture of curatorial whimsy, a large, tightly rendered oil by the mythological Arcadian, Thomas Helms. Although wonderfully adequate, If one goes in for spine-tingling beauty, masterful technical skill, spiritual truth and that sort of thing, It is the unabashed substitution of simplicity for self-absorption which gives the painting its delightful, if occasionally tedious, vulgarity.

In a manner which quaintly unites the humanity of Rembrandt with the line and mysticism of Blake, Helms has depicted an ordinary-looking Jew in a dusty robe who appears to bring a dead man back to life. What might have been embarrassing becomes amusing when one realizes that the content is actually Its punch line. Nevertheless, bringing to bear even the casual discernment of a mature perceptual/contemplative process will lead the well-schooled viewer to the recognition of an intrinsically convoluted orientation in which the apparent meaning of the work is its true meaning, and a framework in which each succeeding layer of thematic elaboration confirms, rather than contradicts or obfuscates its message.

In a less sophisticated era, when objective distinctions were imagined to exist between truth and error, freedom and license, good and bad, It must have seemed possible to gauge the merits of art according to universal values such as theme and variation and the balance found throughout creation between unity and variety. Today, however, when will power plus experience proves that certainty is only ignorance of ambiguity, and when doubting everything, or better, knowing nothing is the sine qua non of the knowledgeable, we must caution that, by including work like Helms’, even the wittiest curator may unintentionally endanger the random (i.e., personal) subjectivity of the selection process.

This is a small matter, however, one which hardly dims the bright prospects of a contemporary museum destined, perhaps, to help quicken the pulse of progress as art continues to move forward in all directions.

While one may say the very presentation of a survey of post-modern art signifies the fulfillment of its purpose, the more important exhibitions function on other levels also. Thus, the Hirsheim-Gebrune not only provides a serviceable visual forum from which to continue refining written commentary on the implications of the pluralistic era Into a higher art form than the art it critiques, its bigness and newness, of course, invests It with the authority to validate those artists deemed to have struggled most successfully to create the trendiest epiphanies, most promising alternatives to reality, cleverest degradations, most urgent banalities, newest expressions of heroic despair (in itself a growing industry), the subtlest derivations, freakiest titillations, coolest esoterica, funniest obscenities and most bankable aesthetic truths. Seeing also that these circumstances enable the credulous many to know what they like and provide the more seasoned few with opportunities to transform their love of art into a profitable emotion, we realize all this helps establish the divine purpose of art (in today’s market).

We applaud the arrival of architecture as proclamation and acknowledge a major new museum’s brilliant initial effort to advance the cultural agenda. In the usual modernist tradition, Zicon-Withpit has insisted on regarding himself as the source of his creativity, with two auspicious results: his achievement marks him as one more candidate for great renown within the contact of the present system, while making it obvious that the circus big top may perform a natural function of the museum, freeing architectural structure to define itself as pure self-expression, unrestricted by purpose.